Lately, I’ve been thinking about the various kinds, or “domains,” of justice that we often discuss in urban planning: spatial justice, environmental justice, transportation justice, housing justice, etc. How are these domains of justice related to one another?

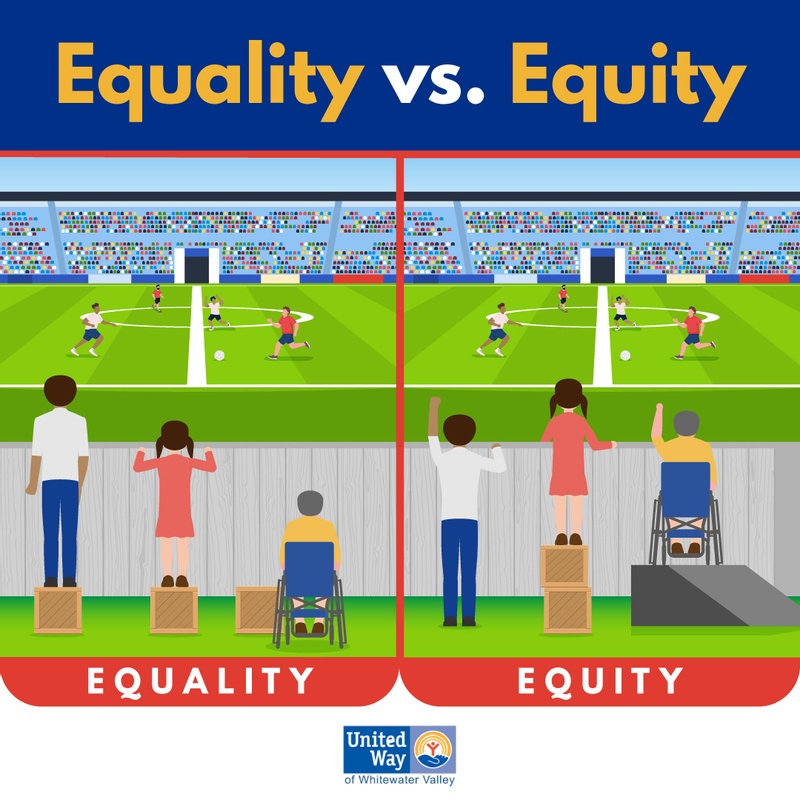

To make things even more complicated, we tend to equate “justice” and “equity” without necessarily probing deeper to see if justice and equity should be distinguished from one another. By now, I’m sure most are familiar with some version of the equality / equity image. This one is from the United Way:

What would a housing justice panel look like? A roof that spans the three spectators? How does housing justice relate to other domains of justice? To sort through this complexity, I decided to create the following Venn Diagram:

I understand justice to be an expression of what we owe to one another as moral equals in terms of actions, goods, or moral attitudes. Justice is the aspect of morality that is concerned with matters of considered judgement that appeal to a publicly justified set of principles that define a society’s terms of fair cooperation. Principles of justice determine who gets what according to these terms of fair cooperation. Racial and ethnic justice are inseparable from justice writ large. Respecting one another as equals requires respecting one another’s differences and treating one other with equal dignity and respect despite those differences.

“Spatial justice”—the overarching category that encompasses all of the smaller spheres in the diagram above—addresses how things should be distributed and arranged in geographic space vis-à-vis the locations of human activity. Spatial justice addresses where things are located at any given point in time and how things flow from one location to another. One could argue that all things are distributed somewhere, so perhaps justice is inseparable from spatial justice. While this is true, not all spatial justice questions are relevant to justice writ large. The question of whether distributive principles should be based on a utilitarian calculus or deontological obligations can be answered independently of where distributive principles are applied, for example.

Environmental justice can be understood as the domain of spatial justice that pertains to the just distribution, arrangement, and flow of natural resources. Whereas spatial justice refers to the distribution of all things that are naturally occurring or produced by human labor, environmental justice is primarily concerned with the distribution of things that are naturally occurring, valued by human beings, and possibly transformed by human production or consumption processes. Most natural resources are nonexcludable (it is impossible or difficult to prevent someone from consuming it) and nonrival (one person’s consumption does not reduce the amount available to others), so environmental justice naturally concerns itself with the distribution of goods that exhibit one or both of these public good characteristics. Because we often believe that everyone should have equal access to a fair share of the earth’s most important natural resources, environmental justice often addresses the question of ownership—who owns the earth, and how do ownership rights get distributed? Environmental justice is also intertwined with racial justice. The spatial correlation between the geography of environmental pollution and the spatial pattern of residential segregation by race implies that people of color often suffer the most severe environmental injustices.

Infrastructure justice is a term that I have not seen elsewhere, but I offer it as a way to characterize the just distribution of publicly financed or publicly owned goods, services, and infrastructure systems. Some infrastructure systems, such as public parks, can be classified as pure public goods, whereas others, such as public water systems that are financed primarily through user fees, may be excludable. The key question for infrastructure systems is whether justice requires that everyone have equal access to a given system, and if so, whether exclusion mechanisms that deny infrastructure access can be justified. Infrastructure justice also overlaps with environmental justice. For example, the recent Flint water crisis was caused initially by a fiscal crisis that triggered a shift in the city’s water supply source that ultimately exposed Flint residents—the large majority of whom were low-income people of color—to dangerously high levels of lead pollution. Infrastructure justice is shaped by fiscal and policy federalism. Questions about the distribution of infrastructure services across space are inseparable from the question of whether decentralized local units of government should have the autonomy to deliver (or not deliver) those services.

Material justice is also a new term (to me at least) that refers to the distribution of particular private goods or services. In contrast to environmental justice, material justice addresses the distribution of goods that are excludable and rival. While distributive justice addresses the distribution of goods and resources in the abstract, material justice is a form of local justice that is grounded, in part, by the nature of the good being distributed within a particular society. A conception of the just distribution of automobiles, for example, should acknowledge the fact that in the US, low-income people who are unable to purchase automobiles may be unable to access other resources and opportunities required to live a flourishing life.

As I see it, housing justice falls at the nexus of environmental, infrastructure, and material justice. Housing provides protection from extreme weather conditions and is often located in proximity to desirable environmental amenities. Homes are also stitched together by networks of transportation, water and sewer, electricity, and broadband infrastructure systems. Some homes fail to offer these services and subject inhabitants to exposure, pollution, or natural hazards. Those whose homes are disconnected from infrastructure systems may be unable to access the same social or economic advantages that are made available to others. The geography of environmental and infrastructure injustice cannot be separated from the discriminatory housing policies that exclude people of color from environmentally healthy neighborhoods and high-quality infrastructure systems.

Materially, housing is a heterogeneous, durable, and spatially fixed good that is distributed in distinctive ways. Homes take several months to construct or retrofit, and once constructed, homes can last for tens or hundreds of years if well maintained. Because the distribution of housing is fixed over the short run, residential relocation and financial compensation are often the only feasible ways to alleviate short-term housing injustices. (Refer to my book, Just Housing, for more on these and other distributive properties of housing.)

This is how I am categorizing things today. I am curious to hear how others categorize the various domains of spatial justice.